Nanjing Atrocities

In the Summer of the year 1937, Japan successfully provoked a full-scale war with China. After an endless number of months dragged on during the battle of Shanghai the Japanese finally conquered the city, they had a frustration burning inside of them because it took much longer than they originally thought to conquer a measly city, let alone all of mainland China (which they assumed would be finished within three months). Soon, Japan turned their frustration on the city of Nanjing.[1]

Situated behind the Yangtze river, this city was home to hundreds of thousands of civilians who were already wary of the struggles of a city existing in a country under siege. After the defeat of Shanghai, the Japanese decided to engage in a full-scale siege targeting Nanjing itself. The plan consisted of the idea that if properly executed, the citizens would be surround by the bends of the river and would have nowhere to go as the Japanese annihilated everything in sight. After the Japanese took the city and cut off means of escape and the possibility of reinforcement, Chinese soldiers began surrendering by the unit. Under typical methods of warfare, and the Geneva convention, unarmed soldiers who submitted themselves for surrender would be taken into custody and placed into POW camps, typically with the intent of being tokens of leverage to trade with China, Chinese prisoners would be traded for Japanese prisoners.[2] This usual method of trading prisoners was thrown out of the window when Japanese forces began to summarily massacre unarmed, frustrated but surrendered Chinese forces.[3] At first, fresh Japanese recruits were hard pressed to conceal their shock at the amount of carnage their own army was committing against the Chinese soldiers and civilians, but one commander wrote in his diary that “all new recruits are like this, but soon they will be doing the same things themselves.”[4]

The atrocities did not stop at the soldiers. Unfortunately, when the armed resistance within Nanjing died after a few months, the Japanese units began to antagonize, rape, torture, and brutally murder the civilians.

Whether or not the civilians put up a fight in order to try and push a hole through the Japanese surrounding the city is certainly a topic to investigate fully, however as far as records show, these civilians were universally innocent and undeserving of the horrific things that were about to happen to them.

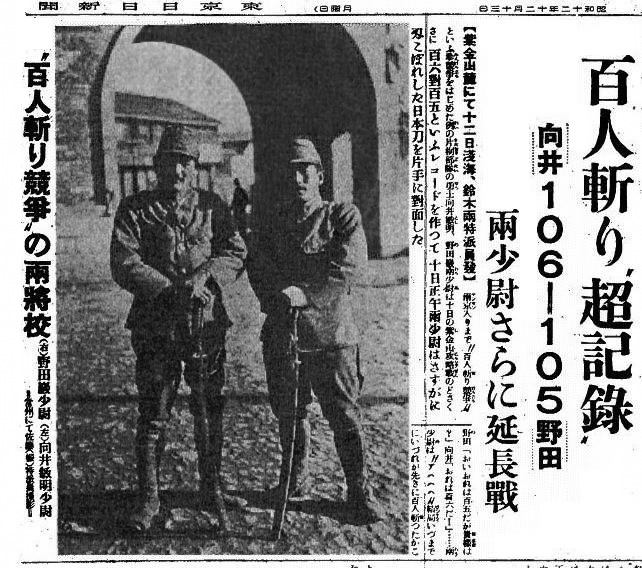

In terms of wholesale murder, the Japanese forces, on the way to Nanjing, typically engaged in a sport of seeing who could murder the most unarmed civilians with a saber. Usually, officers engaged in this sort of competition and murdered dozens if not hundreds of innocent peoples. As horrific as it may seem, these civilians were severed in half, beheaded, delimbed, impaled and brutally slaughtered without so much as a fight.

In addition to the horrific killing contests the officers engaged in during the assault of Nanking, the Japanese army also participated in a series of specific torture methods to be used on the Chinese civilians and soldiers. This list is almost never ending however the ones that historians can point to specifically are as follows; Live burials – buried to their necks and hacked to pieces as they are also trampled by officers’ horses, Mutilation – just as it sounds, people were nailed to boards, ran over with tanks, used for bayonet practice, etc. Death by fire – set ablaze and allowed to continue until all that remained was a charred husk. Death by ice – an unusual one however equally horrific, these people would be freeze to death in frozen ponds. Death by dogs – quite possibly the worst method listed by historians, the Chinese citizens and soldiers were buried to their waist and ripped to shreds by German Shepard’s[5]

One of the main arguments countering typical traditionalist history regarding the massacre at Nanjing says that these claims presented by the victims of the massacre were all a fabrication by the Chinese government to discredit and paint an ogrelike portrait of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

[1] Chang, Iris. The Rape of Nanking. New York. Basic Books. 1997.

[2] Chang, Iris. The Rape of Nanking. New York. Basic Books. 1997.

[3] MARGOLIN, JEAN-LOUIS. "Japanese Crimes in Nanjing, 1937-38: A Reappraisal." China Perspectives, no. 63 (2006): 2-12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24052322.

[4] Chang, Iris. The Rape of Nanking. New York. Basic Books. 1997. 57.

[5] Chang, Iris. The Rape of Nanking. New York. Basic Books. 1997. 87 – 88.

Oral History

According to the testimony of Wen Sunshi, a female survivor of the Rape of Nanjing, one of the most horrific things that could happen to a person had been forced onto her while she was a young woman. Married in 1936 to a man named Guo, Wen lived in Nanking until the massacre had occurred. She had noted that when the Japanese had entered the city of Nanking, the Chinese soldiers began retreating across the river, meanwhile also finding rooms to hide in such as Wen’s home. Wen describes how she was then pulled from a crowd along with several other maidens and taken away into nearby rooms. The disheveled and horrified Chinese woman was then forced to disrobe at knifepoint and summarily raped by a chubby Chinese foot soldier with a beard.

After Wen was raped by the Japanese soldier, she was free to go. “opened path, open path,” the Japanese said and opened the door for her. Wen told her husband what had happened to her that fateful day, however, she has never told her sons and daughters, according to Wen, she was afraid that her children might be disgusted with her if the secret ever slipped.

Wen also described that elderly neighbors, who thought they were safe and could remain home were brutally murdered by the Japanese invaders without hesitation. Wen also had a cousin dragged away by the Japanese, never to be seen again.

Wen suffered greatly at the hands of the Japanese. Despite her being alive today, she carries a burden that those who were massacred do not have to endure to this day. Being violated at knifepoint by a Japanese soldier has warped her life to never be the same again. A mix of shame and denial permeates throughout the rest of the testimonies of the survivors as they perhaps wished they could have died during the massacre rather than live with the memory.[1]

[1] ""I Will Never Forget": Voices of Survivors." Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed November 20, 2018. https://www.facinghistory.org/nanjing-atrocities/atrocities/i-will-never-forget-voices-survivors.