Discrimination in World War

Discrimination in World War II

By: Anjelica R. Garza

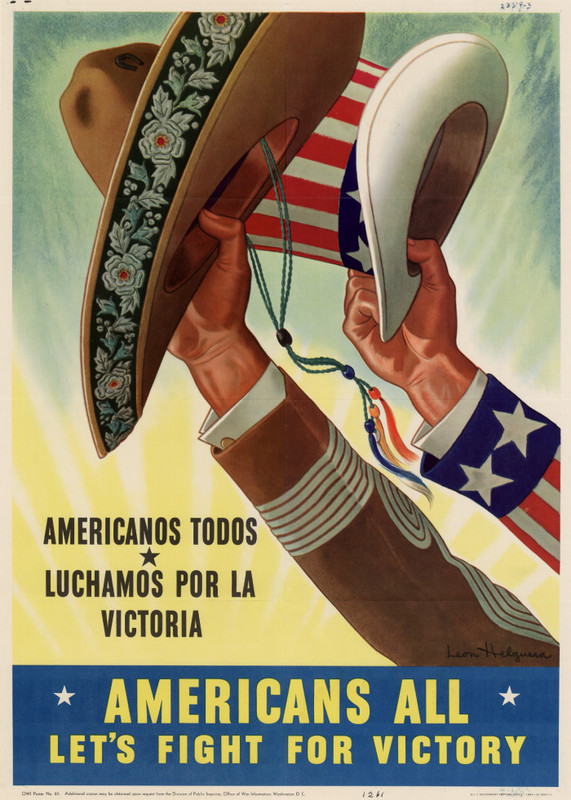

During World War II there were between 250,000 and 500,000 Latinos serving in the military. Latinos had been discriminated against long before World War II happened but this was different. War can bring together people from all walks of life in order to reach a common goal. During the World Wars, total war became prominent. Total War is defined as a war, encompassing all forms of people in their respective country. Civilians are drafted, work in factories, or buy war bonds to help support their country. Military efforts are directed at the current battle front, the opposing countries civilian populations, the opposing countries economy, and the opposing countries morale. Suddenly the war has encompassed all aspects of day to day life and propaganda was found everywhere. In order to really help their country all forms of men are drafted including men of color despite any racial beliefs. Beforehand Latinos had served in wars but they were not recognized nor were they treated fairly. Latinos were discriminated against based off of their language and heritage.

Latinos have fought in a number of wars, for the United States but this was the first time they were recognized in such large numbers. There is documentation that Latinos fought in World War I, but their numbers and movements are unsure. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor men were drafted by the dozen to serve in various branches of the military. Latinos were not forced into segregated units like African American soldiers were, but many rushed to enlist. Like other soldier’s Latinos were sent to bases for basic training where they experienced the same training as other soldiers. However, because of their race, remarks or sometimes even actions were made. Cultural barriers as well as language barriers separated these Latino soldiers from soldiers of other races. Discrimination was felt in the barracks, in the battle field, and on the Homefront.

Several soldiers experienced racism due to language barriers. Many Latinos grew up speaking only Spanish with very little conversational English. After joining the military there was a rush to learn so that the soldiers could perform and follow orders. Natividad Campos was a Private First Class in the Army when he experienced racism via language “’When [Latinos] got together, we would automatically carry a conversation in Spanish, not in English, because we weren’t very professional in English,’ said Campos about his recollections about the Cavalry. ‘So [the white soldiers] would give us hell and say ‘you’re in the American Army, speak English.’ So I spoke English.”[1]There were never official offenses for speaking Spanish but white soldiers would heavily insult Latino soldiers for speaking Spanish.

While other men could speak English, some had very noticeable accents. Luis Alfonso Diaz de Leon was quartermaster of his ship in the navy. The quartermaster’s duty was to steer the ship and make announcements over the ships loudspeaker. After making his first rounds Diaz de Leon remembered this happening “a group of fellow soldiers asked if he’d been the person talking over the loudspeaker. With pride and a sense of accomplishment, Diaz de Leon answered yes, anticipating congratulatory remarks. Instead, he says he received racist insults. Apparently, at one point he’d said, ‘darken sheep’ when the message he meant to convey was, ‘darken ship.’”[2]Despite this encounter Diaz de Leon was approached by one of his superior officers who offered to teach Leon better English pronunciation if Leon would teach him conversational Spanish.[3]

There was hatred based off of stereotypes concerning the Zoot Suit Riots in the 1940s. The Zoot Suiters were young Mexican Americans who had formed social groups, or as some would call it gangs, in their communities. These young men and women were often seen as disrespectful, vivacious, and as miscreants. There are very few recorded instances of Zoot Suiters participating in traditional gang activity, except for the Sleepy Lagoon murders in 1942. After Jose Diaz was found murdered 22 members of the 38thstreet gang were arrested and later prosecuted. Though this was one of the few public instances of Latinos fulfilling a stereotype it left its mark.[4]By then nearly all Latinos began to feel more discrimination from Anglo Americans especially from Anglo servicemen. Hermenejildo Salas was a private in the Marine corps and he recalls “’We had brawls all the time,’ said Salas of his basic training days. Due to the local Zoot Suiters, who’d attacked servicemen when they were on liberty, Salas says he learned quickly not to go into town alone.”[5]

Because of such discrimination Latinos found it hard to enlist or increase their status in the military. Some were initially turned away until the government issued the general draft. Leno Flores Diaz remembers that “When the United States entered World War II in 1941, he says he tried to enlist, but was turned away from every military branch. ‘I was a Mexican national, that’s why I was not accepted,’ he said. ‘I felt real strongly that we were fighting enemies that were really trying to destroy us. . . Although I was not an American citizen, I felt that I wanted to go. . .Living in the ghetto I couldn’t get ahead, and that too prompted me to try to be accepted in all the branches.’ He later added ‘I could have returned to Mexico, but I didn’t. That was the cowards way.’”[6]While men like Leno felt very strongly about serving in the military not everyone did. Some were just plain confused. After all, why fight the war of a country and people who do not accept you? At this time, Latinos were struggling to create an identity for themselves so when the subject of World War II came up some just didn’t know what to think.[7]Alberto Lara Rojo chose to enlist in the navy after experiencing much confusion “Other Mexican American students told him, ‘It’s a gringo war. It does not affect us Spanish people.’”[8]Needless to say Alberto was very confused on the matter.

Latinos were discriminated against based off of their language and heritage. Many Latinos were raised speaking English and Spanish while some only spoke Spanish. This was intended to help them since they were surrounded by other Latinos for most of their lives. Until World War II that is. After enlisting in the military, Latinos learned very quickly that things would not be as they were before. If someone had a Spanish accent, darker skin, or a Spanish sounding name then that gave Anglo Servicemen as well as civilians cause to mock them. General confusion surrounded the war effort. Most didn’t know if they would enlist, get drafted, or what was even the point. However, in Rojo’s case his father had served in World War I and had taught Alberto that serving in this countries time of need was necessary for the future. It may be bad now but it will be better in the future. Starting with us.

Oral History of Peter Salcedo

Peter Salcedo was born and raised in Sespe. California. One of his most prolific memories was the Mexican food his mother would make him for lunch. As a child, he attended a segregated but primarily white school. While it was common for children to bring lunch from home the other children brought common food such as sandwiches, fried chicken, vegetables, and fruits. Whereas Salcedo would bring tacos which was very unknown at the time. He recalls that there were few Mexican restaurants at the time so his food was unique and marked him as a Mexican.

After spending days in school where English was spoken Salcedo began to lose his knowledge of Spanish. When he’d come home his parents would speak Spanish but he’d have to answer in English. It wasn’t until much later when Salcedo met and married his wife Maria that his Spanish began to improve. After hearing about Pearl Harbor, Peter Salcedo decided to serve in the Navy instead of going with his family to Mexico. While there Salcedo experienced racism amongst the sailors. Salcedo’s childhood friend Felix Salvador was half African American and half Filipino for which he received very discouraging remarks. Some even went far enough to call Felix “dirty” simply because of his mixed heritage. After experiencing such unrestrained discrimination Salcedo decided to quit the Navy only to later join the army and become a colonel. Of course, that didn’t stop the racism. While being stationed in Hawaii, Salcedo would share a tent with a man from Texas who would make very openly racist remarks about African Americans and Latinos. This experience caused Salcedo to fear Texas until he would visit Texas and have a pleasant experience.

While in Hawaii Salcedo’s main job was fixing the military ships that would enter the harbor for 18 months. After contracting a terrible foot fungus Salcedo would be discharged from the military in 1946. After being discharged Salcedo would only see the negative aspects of war and would work very hard to get another job. Even though Salcedo was offered his old job at the Trim’N Drill his pay would be cut from $1.03 per hour to 75 cents which would lead to him looking for jobs elsewhere. But because Salcedo had dropped out of high school it was very difficult for him to find a well-paying job that was willing to hire a Latino. After switching jobs, many times Salcedo would eventually become a painter and earn his high school diploma. With his wife Maria, Salcedo would have three adult children Betty Jean Johnson, Peter Jr., and Mariano. When asked if he had any regrets his answer was dropping out of school and taquitos.

[1]Natividad Campos, interview by Beatriz Guerrero. Oral Interviews. VOCES Oral History Project, Austin Texas.

[2]Luis Alfonso Diaz de Leon, interview by Raquel C. Garza. Oral Interviews. VOCES Oral History Project, Austin Texas.

[3]Luis Alfonso Diaz de Leon, interview by Raquel C. Garza. Oral Interviews. VOCES Oral History Project, Austin Texas.

[4]Catherine S. Ramirez, The Woman in the Zoot Suit: Gender, Nationalism, and the Cultural Politics of Memory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 1-23.

[5]Hermenejildo Salas, interview by Chris Riley. VOCES Oral History Project, Austin Texas.

[6]Leno Flores Diaz, interview by Raquel C. Garza. Oral Interview. VOCES Oral History Project, Austin Texas.

[7]Vicki L. Ruiz, From Out of the Shadows (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 45.

[8]Alberto Lara Rojo, interview by Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez. VOCES Oral History Project, Austin Texas.