Propaganda in Java During the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

Propaganda as a Vehicle of Implementing the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

by Harley Mathews

The role of the individual propagandist in the implementation of supporting the efforts of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity sphere is key to understanding the overall direction of the war and its uses. Looking specifically at the propaganda in Java will give an acute experience in the propaganda, the propagandist, and the responses to the material. Media varying from paper flyers, film, newspaper, puppet plays, etc. The primary sources used to distinguish specific examples of propaganda in this research focus on cultural medium that is closest to the people being colonized, as well as the responses about the propaganda and use of American news as propaganda in Java and other countries during the Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere period. Propaganda used in Java will clearly determine that the war efforts were fought not in stages but in a takeover of media and battery of material to all parts of colonized communities as its own form of warfare.

Initiating an understanding of propaganda must include some details about who a propagandist is and is not. Initially, set up as a station and department of war in Java, it was presented as a civilian task, though the “Japanese authorities never trusted control of this department to civilian hands”.[1] This would mean militarizing the media in every form. Where use of force is not a valid option, the use of strongly vetted individuals with propaganda jobs was put at the forefront of Java’s experience with Japanese colonization. Five sections are specified according to primary sources from Java; “administration, literature, music, fine arts, performance arts (theatrical plays, dance, and film).”[2] Who would fill these roles would be determined by a few factors, specifically their anti-Dutch sentiments, their personalities, skills in public life, popularity, and various other categories of interest when building these military-sanctioned propaganda machines. A clear distinction is seen here between some paper flyers being distributed to introduce themselves and a machine as valuable to the Japanese empire’s overall goals as tanks and railroads and guns are. A prime example of Japan’s emphasis on what is allowed is its takeover of film in the movie policy in Java, which was modeled after Japanese policy in China. The policy included setting up an official list of movies permitted by the “Japan Motion Picture Company”, which was built and distributed from Tokyo, and included the change from an emphasis mainly of American movies in popularity and viewings to “fifty-two Japanese, thirty-two Chinese, and six Axis films annually.”[3] The most common films shown in Java before were always American films, something that would define influence and support for empathy rather than pro-Japanese ethic that is necessary for the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere to take shape.

In the example of the popular cartoonist Yokoyama Ryuichi, even the goals of the military in employing propagandists in Java and elsewhere was something of an imbalance, though still useful. A war cannot be won solely by guns and ammunition, and Japan excelled with the use of both local and Japanese artist, poets, filmmakers, and others who would help to persuade the population of Java. Ryuichi’s attitude of the job was one of an overall pleasant experience, even when under duress.[4] He was clear in understanding that he was being used as a tool, and would do his job and produce what was asked and use the time otherwise to see the culture.[5] (Cook and Cook 98) His audience as already developed in Japan through his popular cartoon Fuku-chan, but his exposure to specifically common people in Java, housewives for example, implies a need for propaganda in the household as well as the public space. The images that come to mind of movies where there are endless flags and posters the size of whole walls is not as effective as the slow and subtle work done to keep the dominating culture on the tongue of each family member.

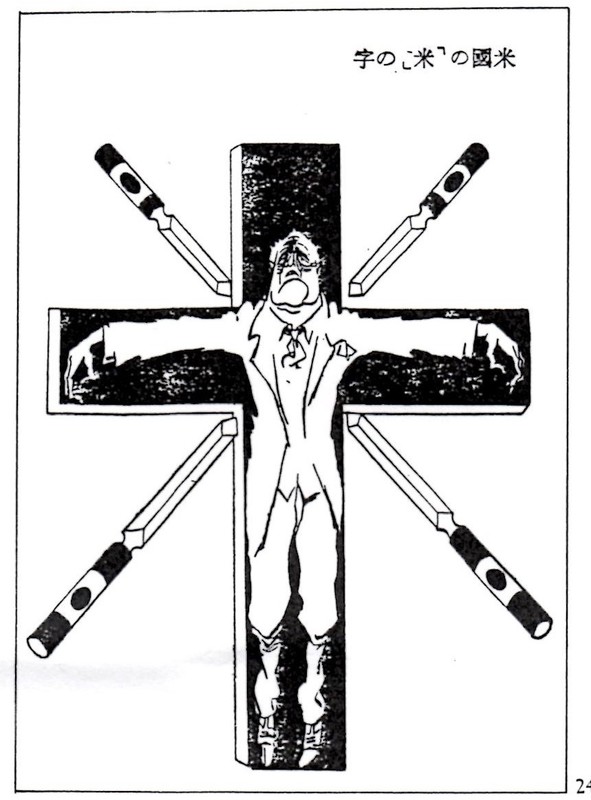

Beyond information persuasion is the articulation of power for the Japanese through images. As an example of a clear and distinct use of strong images as a way of interpreting message and themes of Japan and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity’s goals, the image on the right was produced in Osaka Puck magazine. It is just as important to dishonor the resident images and philosophies of Western culture as it is to establish a new one. The image of Theodore Roosevelt crucified with four bayonets pointed in his direction is the use of a Japanese kanji for beikoku which is used for America. Using the word itself as a tool with caricatures of the American rhetoric emphasizes for the viewer, even the one who doesn’t read Japanese, that America has totally different models for ethics and will not succeed under higher authority. The use of the bayonet’s, a common tool throughout the battles during both wars, is overseeing the false religion of the American value system. For a country like Java, the articulation of religious values and a realignment that could mean a return to the citizen’s chosen religions would be appealing without explanation. This value, the ability to speak without training in various dialects and whole languages is key to the success of propaganda.

As a point of irony, the Japanese did allow specific information about the United States through a specific lens of interpretation. Reports were commonly recorded and released by Japan in other countries they had occupied via radio broadcasts. Joel V. Berreman researched and interpreted these as assumptions using primary sources towards the end of the war in his research. One strong example is; “There can be no question but that war was forced on Japan by an arrogant and dangerous enemy who has no hesitancy in resorting to any trick of propaganda to attain his sinister end...by November 26, 1941 the United States…a state tantamount to war against Japan.”[6]

First, and at its base level, propaganda presented to Java from Japan was a way to encourage pro-Japanese sentiment in the native communities while they are being colonized. “To the enemy [Japan] news is a weapon of war…The Japanese, closely copying the Nazi system of propaganda, are intensifying their efforts. Since it is an avowed concept of these three war-making governments that propaganda is one of their most powerful instruments, they have no fondness for anyone who interferes with their effort.”[7] The strength of this process is understood by way to instituting minor allegiances and areas of ‘authority’ that is under Japanese guidance interpreted to become independence. “In Malaya, Java, Borneo, and Sumatra, still governed by the Japanese military, provincial councils have been set up composed of native people…hints at independence for full cooperation with the Japanese.”[8]

Using primary sources published in 1944, Berreman specifies an overall look at how Japan was interpreting America to colonized people. These caricatures would be two fold, to instill new imperialist perspectives about Asia as superior to America and Britain as well as to encourage more of an already turbulent attitude in Java towards the British and her allies. “The Atlantic Charter is a “false from for Anglo-American imperialism”.[9] On August 15, 1943 a more specific call about the Charter would emphasize “The Charter says that people should have the right to choose their form of government. The leaders of India believed that and are now in jail. As Churchill said, he did not become prime minister to preside over the dissolution of the British Empire.”[10]

What this means for Java, and is replicated in other occupied countries, is a replacement of news. “In January 1943 the Tokyo radio proclaimed to the Japanese people: "The Greater East Asia War is a war of thought and culture as well as a war of armed forces. . . The Philippines, Malaya, and Java were formerly under the rule of America, Britain, and the Netherlands respectively, and consequently the inhabitants of these territories are deeply imbued with American, British, and Dutch ideas. It is true they have been freed from the political influences of these enemy countries, but they have yet to be thoroughly purged of their ideological influences."[11] The use of “purge” here is a bit dramatic, because the news that was released included commentary on the United States and the strength and longevity of Japanese values. “After twenty years of soft living the American soldiers are no match for the Japanese [2-11-43]” emphasized the perspective and needed deprecating attitude towards Axis troops.[12] Attaching this repeated image on radio broadcasts with messages about “the burning internal unity of the Japanese gives them a mental energy eternally beyond America’s materialistic logic”.[13]

The overwhelming nature of war cannot be understood only within the context of military expansion, death tolls, but must include ethics and the proselytizing nature of control. Japan fought a war as cognitively damaging as it did in what is often included as ‘spoils of war’ in regards to captures and death tolls. Colonization in the mindset of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere ethos is one that puts the battle first and foremost in the minds of those being colonized. The introduction of material and interactive elements that would devalue their current leadership as well as induce a feeling of being taken care of and levels of independence kept Japan in control of Java and other countries using propaganda as its strongest of weapons.

[1] Aiko Kurasawa, “Propaganda Media on Java under the Japanese 1942-1945” Indonesia, No. 44 (October 1987), 60.

[2] Kurasawa, “Propaganda Media,” 62.

[3] Kurasawa, “Propaganda Media on Java,” 68-69.

[4] Yokoyama Ryuichi, Cartoons for War, from Japan at War: An Oral History, ed. Haruko Taya and Theodore F. Cook (The New Press: New York 1992), 97.

[5] Yokoyama Ryuichi, Cartoons for War, 98.

[6] Joel V. Berreman, “Assumptions About America in Japanese War Propaganda to the United States,” in American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 54, No. 2 (Sept. 1948), 110.

[7] Matthew Gordon, “What the Axis Thinks of the OWI,” in The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Spring 1943), 134.

[8] Joel V. Berreman, “The Japanization of Far Eastern Occupied Areas,” in Pacific Affairs, Vol. 17, No. 2 (June., 1944), 169.

[9] Berreman, “Assumptions About America,” 109.

[10] Berreman, “Assumptions About America,” 109.

[11] Berreman, “The Japanization” 169.

[12] Berreman, “Assumptions,” 112.

[13] Berreman, “Assumptions,” 112.

Oral History – Cartoonist for the War by Yokoyama Ryuichi

Source: Yokoyama Ryuichi, Cartoons for War, from Japan at War: An Oral History ed. Haruko Taya and Theodore F. Cook (The New Press: New York 1992).

Yokoyama Ryuichi’s role in the period of promoting the war known as the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere is one that is often ignored for the more dynamic elements of soldiers and military tactics, but is not less important in the manufacturing and maintaining a strong ethic of war. In his oral history Cartoons for the War we are able to see (1) the propagandists life and perspective rather than just a caricature of war, a fair scope of (2) his audiences, as well as (3) his work in propaganda. Ryuichi’s attitude towards war is one of vocation rather than devotion and will allow a clearer view of propaganda’s use, creation, and strength in a spread of the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.[1]

Ryuichi’s character Fuku-chan was immensely popular with the Japanese public and continued even after the end of the war. His work was mostly cartoons in the ‘family section’ of the newspaper, never intended for children, but never provocative enough to be challenged as counter-ideology, making him a prime candidate for being a propagandist.[2] He cites his work with paper plays to people in Java, a well-studied country in regards to their use in propaganda. “I showed paper plays to people in Java…that showed how just and strong the Japanese military was…an advertising job.”[3] The audience of Ryuichi in Java under the occupation and evaluation of the Japanese has implications of language barriers and a broad scope of propaganda use. An easy assumption that propaganda was for the elite and important portions of the communities being occupied is dismissed through this oral history. For the Japanese, the rural and urban citizen should understand that the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere is their fortune, their responsibility, their blessing in uniting Asia for Asians.

The personal attitude of Ryuichi, the war efforts through propaganda themselves in scope, and the medium chosen are all integral to understanding the efforts of Japan to through stages and direct impact remove pro-western ideals, educate the populous about Japan in the best possible light, and increasingly find themselves as full authority in the regions that would move from temporary to fully controlled by Japan. The propaganda, in the hands of reluctant or fully supportive propagandists, would change the war in the senses of the ability to persuade and interpret the colonized population through reaction and acceptance of values and false promises of freedom.