The Lesser Known Japanese Internment

Humberto Garcia

The internment of Japanese immigrants and Japanese-American citizens in camps during World War II by the United States’ government, was and continues to be a scourge on the nation’s history. While these injustices are starting to become more familiar to the national historical narrative, they were not exclusive to Japanese immigrants or American citizens. The imprisonment of Peruvian-Japanese deportees within the nation’s only family internment camp in Crystal City, Texas, is one such example. The deportees were viewed as a threat to both Peru and the United States before and after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. The two nations then sought to benefit economically and diplomatically from Peruvian-Japanese citizen and immigrant internment. In both cases, race and prejudice played essential roles in their road to deportation and treatment before, during, and after incarceration.

Prior to the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, the nation of Peru implemented legislation in order to curb Japanese immigration into its borders. Anti-Japanese sentiment had risen in Peru due to, “the economic success of Japanese farmers and businessmen.”[1] These successes led the Peruvian people attack Peruvian-Japanese citizens and their businesses. The racial motives of the malice towards their fellow countrymen were unique during this time because “in Peru there was discrimination according to social class but, unlike the United States, there was no strong tradition of discrimination based on race.”[2] The prejudices encountered began to take their toll on the Japanese populace well before the attack on Pearl Harbor, however, not before the Peruvian government helped drive a wedge between itself and its Peruvian-Japanese citizens.

In 1937, the government of Peru passed a decree revoking citizenship rights of Peruvians who had Japanese ancestry followed by a second decree making it even more difficult to maintain citizenship.[3] Peru’s anti-Japanese stance and legislation may not have been fully of their own volition. Pressure from the United States was seen as an influence for Peruvians’ “anti-Japanese attitude” against their own citizens.[4] Given these circumstances, when the opportunity to rid themselves of their economic rivals presented itself, Peru’s government willingly deported their Japanese foreign and domestic born inhabitants.

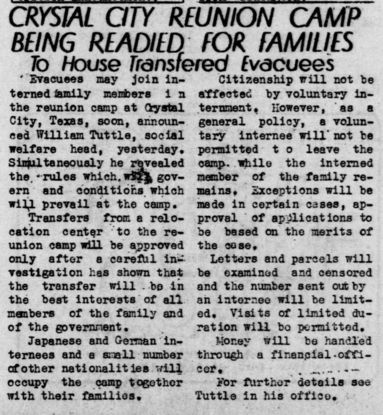

From 1941 through 1946, The United States took in “approximately 2,300 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry who were abducted from 13 Latin American countries and deported to internment camps” during World War II.[5] The majority of those abducted and interned were from Peru. The Peruvian government’s eagerness to rid themselves of their Japanese populace was only matched by the U.S. government’s eagerness in “sending troop transport ships to Lima, Peru.”[6] Although the Japanese-Peruvians posed no real threat to the United States, their internment was seen as diplomatically beneficial. The U. S. involvement in World War II guaranteed many of their military personnel would be captured by enemy forces, therefore, the Latin-American Japanese abductees served “as bargaining chips for U.S. soldiers who might be captured by the Japanese military.”[7] The racially motivated incarceration of Peruvian-Japanese citizens continued to unfold in Crystal City, Texas.

Used to their own lifestyles and customs, the internment camp of Crystal City, Texas provided a culture shock to its inhabitants. One internee expressed surprise at the size of their living quarters, “it just seemed impossible that we would be living in, in a duplex like that. It was small!”[8] The small spaces in which the internees had to make due, were exacerbated by their shoddy construction and the sweltering Texas summers. Higashide recounts his experiences in the housing,

The one significant inconvenience we all faced was the flimsy barracks, built with uninsulated roofs and walls. In mid-summer, the barracks became a hellish oven. Constructed of thin plywood, the barracks stood in the middle of a desert where in summer temperatures reached 120 degrees Fahrenheit outdoors. In such ferocious heat, it became so hot that we were blistered if we touched metal parts.[9]

Nonetheless, the Peruvian internees made due with what they had and their children became friends with the Japanese-Americans’ children who also inhabited the camp. This was partially because of their attending one of three different language-based schools (English, Japanese, and German) within the camp. With no school available for the predominantly Spanish speaking Peruvians, many opted for the Japanese school.

It is here where Bessie Masuda, a predominantly English speaking, Japanese-American citizen recalls her friendships made with some Peruvian children, “I spoke English and [the children from Peru] spoke Spanish [but in Japanese school] we had to speak Japanese.

But, they [would] speak [Japanese] with a Spanish accent. They would laugh at me and I would laugh at them.”[10] While it may seem like the Peruvian-Japanese children were enjoying themselves in Crystal City, they endured unnecessary hardships. Inadequate facilities and negligence were problems many internees faced. These problems even led to the deaths of several Peruvian citizens. One of the daughters of a Peruvian-Japanese internee somberly reflected, “During internment, my father's wife died in that Texas camp due to the trauma of imprisonment and lack of adequate medical care.”[11] Negligence also played a part in Bessie Masuda’s Peruvian friend drowning in the internment camp’s swimming pool. After a failed attempt to save her was made by Masuda and friends, “it was too late to call for help.”[12] These were only a few injustices forced upon the Peruvian-Japanese populace.

Of the over 2,100 Latin-American internees located in the United States, “84 percent were from Peru.”[13] The end of World War II saw the halting of the hostage exchange program conducted by the United States government. Still the Crystal City internment camp saw 300 Peruvian-Japanese citizens declared illegal aliens by the United States government and unwanted in their native country of Peru.[14] The great injustices heaped upon them by the racial policies of two allied nations should never be ignored, forgotten, or silenced.

Bibliography

Barnhart, Edward N., “Japanese Internees from Peru.” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 31, No. 2 (May, 1962), pp. 169-178.

Garcia, Guillermo X. "PRISONERS OF WAR // Texas Camps Held Hostages of WWII Hysteria." Austin American Statesman, Sep 18, 1989. Accessed 12 November 2018.

Higashide, Seiichi. Adios to Tears: The Memoirs of a Japanese-peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps. Seattle: Univ Of Washington Press, 2011.

Masuda, Bessie., "Experiences at Crystal City,” transcript of an oral history conducted 2011 by Lara Newcomer, Texas Historical Commission’s Texas in World War II

Initiative, Austin, Texas, 2011, 24 pp.

TREATMENT OF LATIN AMERICANS OF JAPANESE DESCENT, EUROPEAN AMERICANS, AND JEWISH REFUGEES DURING WORLD WAR II. March 19, 2009. Accessed November 11, 2018.

[1] Edward N. Barnhart, “Japanese Internees from Peru.” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 31, No. 2 (May, 1962), 169.

[2] Seiichi Higashide, Adios to Tears: The Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps, (Seattle: Univ Of Washington Press, 2011), 102.

[3] Barnhart, “Japanese Internees from Peru,” 99. 169-170.

[4] Higashide, Adios to Tears, 104.

[5] TREATMENT OF LATIN AMERICANS OF JAPANESE DESCENT, EUROPEAN AMERICANS, AND JEWISH REFUGEES DURING WORLD WAR II, March 19, 2009, , accessed November 13, 2018.

[6] Guillermo X. Garcia, "PRISONERS OF WAR // Texas Camps Held Hostages of WWII Hysteria." Austin American Statesman, Sep 18, 1989.

[7] Garcia, “Prisoners of War,”

[8] Bessie Masuda, “Experiences at Crystal City,” transcript of an oral history conducted 2011 by Lara Newcomer, Texas Historical Commission’s Texas in World War II

Initiative, Austin, Texas, 2011,19.

[9] Higashide, Adios to Tears, 167.

[10] Masuda, “Oral History,” 8.

[11] TREATMENT OF LATIN AMERICANS OF JAPANESE DESCENT, EUROPEAN AMERICANS, AND JEWISH REFUGEES DURING WORLD WAR II, March 19, 2009, , accessed November 13, 2018,

[12] Masuda, “Oral History,” 13.

[13] Higashide, Adios to Tears, 177.

[14] Higashide, Adios to Tears, 177.

Oral History

“Bessie Masuda Experiences at Crystal City”

Bessie Masuda’s experiences as a Japanese-American citizen imprisoned in the Crystal City internments camps are transcribed within this oral history. Born in Stockton, and raised in a grape farm in Lodi, California, Masuda recalls the FBI raid leading to her father’s internment and the trauma her family endured.[1] (3-4). While her father was incarcerated her family was moved to the Stockton Assembly Center before being transferred to Crystal City internment camp, two years after her father was abducted.[2] (6-8) Imprisoned alongside her family, Masuda, in her early teens, discusses her experiences within the walls of the camp. With repatriation in mind, Masuda’s family has her join the Japanese language school in order to learn the customs, traditions, and language of a country she is not familiar with.[3] (8) It is within the walls of the school where she befriends several Peruvian-Japanese students, and experiences trauma when trying to save one of them from drowning.[4] (13) Masuda, also goes into detail about her family trying to rebuild their lives in San Francisco after leaving the camp.[5]

[1] Bessie Masuda, “Experiences at Crystal City,” transcript of an oral history conducted 2011 by Lara Newcomer, Texas Historical Commission’s Texas in World War II

Initiative, Austin, Texas, 2011,pp. 3-4.

[2] Masuda, “Experiences at Crystal City,” pp.6-8.

[3] Masuda, “Experiences at Crystal City,” 8.

[4] Masuda, “Experiences at Crystal City,” 13.

[5] Masuda, “Experiences at Crystal City,” pp. 14-15.