Cisneros v. Corpus Christi ISD

By: Eric C. Hernandez

The Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District (CCISD) case and its ruling by District Court Judge Woodrow Seals in 1970, in favor of the plaintiffs, is a landmark case for Mexican American civil rights. In 1968 Jose Cisneros, after two years of pleading with the administration at CCISD to fix up the minority-majority schools where his children attended along with over two dozen other parents of students at CCISD’s schools decided to take legal action and retained lawyer James De Anda, who formally filed a lawsuit against CCISD.[1] De Anda would use the rationale of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling from 1954 to establish Mexican Americans as an identifiable minority group and prove that segregation as well as discriminatory practices had been perpetuated and implemented knowingly by CCISD administration against Mexican American students. The result of this court case would be an integrated school system where segregation and discrimination would not be tolerated.

Mid-twentieth century South Texas was a much different environment than what is seen today. In 1910 when the Mexican Revolution began thousands of Mexican refugees sought opportunity crossing the border and seeking out a better life, and by the 1950s, postwar Mexican immigrant populations, included native born Tejanos who shared language and culture, numbered over a million.[2] Discrimination against Mexican immigrants became common place throughout the area known as the Nueces Strip, the stretch of land from the Rio Grande River continuing north to the Nueces River, where they worked on ranches or farms for extremely low wages and sub-human living conditions. The distinction between native born Tejanos, with their shared culture, and Mexican immigrants became blurred and soon led to Tejanos being pulled under the same discriminatory umbrella employed by Anglo citizens. Corpus Christi, like many other South Texas towns and cities, being no stranger to discrimination engaged in its practices all the same, perpetuating the social narrative that those of Mexican origin or Hispanic ethnicity were second class-citizens. [3] In a report from a Mexican consul in Corpus Christi to his superiors in 1949 he reports that discrimination occurred daily and its legal forms permeated everywhere including schools, public places and housing. This kind of discrimination worried the consul because it was enforced by the law.[4] Deeds for homes in the nicer part of the city would exclude anyone who was not of the Anglo race; this type of discrimination made it very simple for attendance lines to be drawn to mimic the residential segregation in CCISD's school system. Mexican Americans civil rights were being ignored as they were treated like second-class citizens, however this would soon become a legal matter with the passing of the Civil Rights Act.

In 1964, only four years prior to the case Cisneros case was filed, the Civil Rights Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, which forbade discrimination based on race, sex, religion and national origin. It also authorized the withholding of federal funding for any state still engaged in acts of discrimination and segregation. In 1954 when the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that separate but equal is inherently unequal and segregation in public school systems was unconstitutional, the court offered no plan to effectively implement desegregation.[5] Thus the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) set forth goals and guidelines for school districts to desegregate and had their Office of Civil Rights conduct investigations on alleged discrimination in school districts where discrimination was reported. The statistics were collected and published but only in categories of “white” and “black.”[6] Since Mexican Americans were legally defined as “white” it was simple for school districts to claim desegregation by enrolling more Mexican American students at formerly all-black schools. This exemplifies segregation in the acknowledgment of the legal white status of Mexican American students being exploited and the school districts willful disregard to enroll any Anglo American students in formerly all-black schools. This was made even easier by the attendance lines drawn by CCISD and the residential divides that emulated the segregation in the schools in the actual residential patterns of Corpus Christi at the time.

Jose Cisneros children, who were enrolled in the formerly all-black schools, complained to their father about the schools run down condition and overall sanitary issues. This led Cisneros to request the school board to allocate funds to fix the schools around the city that were broken down and in need of repair. After two years of refusal from the school district to acknowledge his request, Cisneros sought counsel with Civil Rights Commissioner Dr. Hector P. Garcia.[7] After a year-long investigation conducted by the Department of HEW at the request of Dr. Garcia they concluded that CCISD had violated both the Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.[8] After CCISD refused to implement the desegregation proposals from HEW, Cisneros decided to pursue legal action, but this time he and a group of parents whose children also attended similar schools banded together, retained lawyer James De Anda, and filed a class action lawsuit against CCISD. The court hearings began mid-May of 1970 and De Anda would prove that Mexican Americans were in fact an identifiable minority that had suffered discrimination and segregation at the hands of Anglo Americans and deserved the same protection as African Americans under Brown.

In the hearings, De Anda argued that CCISD had done everything in their power to slow down and limit integration such as enrolling Mexican Americans in formerly all-black schools to satisfy desegregation, to implementing judicially approved freedom of choice plans. These plans in particular prohibited Mexican American students from enrolling at formerly all-white schools since they were already enrolled in “white” schools; the Mexican American students being the “white” population at these schools. He argued that the percentages of ethnic population broken up into Anglo Americans, Mexican Americans, and African Americans, enrolled across the school district did not reflect actual student body populations. Out of the 9800 enrolled students in CCISD's high schools, 1300 Mexican Americans and 200 African Americans attended schools with greater than 90 percent non-Anglo populations; 32 percent of Anglo American students enrolled in high school attended schools with 20-30 percent or less non-Anglo populations. He insisted that integrated school systems reflect the ethnic populations at all schools across all grade levels and should approximate student body population, but they did not.[9] De Anda connected the unequal student enrollments with the residential boundaries and attendance boundaries drawn by CCISD and made a point in reminding the court that certain residential areas originally had deed restrictions limiting ownership to members of the white race. Since there were very few if any Mexican American families who lived in these predominantly white areas, it was fairly easy for De Anda to show how segregated boundaries in residential areas were being implemented in the school district.[10]

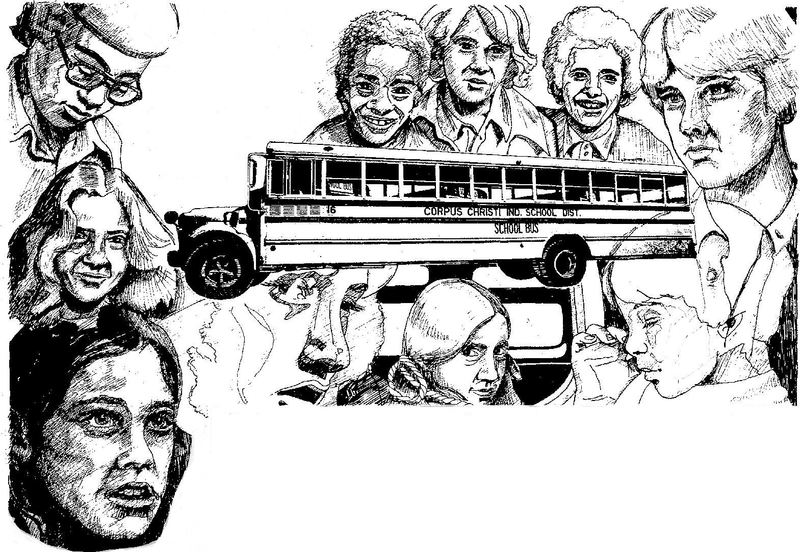

On June 4th 1970, District Court Judge Woodrow Seals ruled in favor of the plaintiffs declaring that the official decisions of CCISD were “calculated to, and did, maintain a dual school system.”[11] In 1975, it fell on Judge Owen Cox to oversee the court ruling for integration of CCISD and the court ordered busing plans to be implemented. Buses would bring African American and Mexican American students across town to formerly all-white schools and vice versa.[12] There were those who opposed the busing plans, mainly Anglos but some Mexican Americans as well. By 1977 however, the anti-busers had come to the conclusion that integration was going to happen despite their best efforts to prevent it through court appeals and even boycotts.[13] Ten years had passed since De Anda had been retained by Cisneros and the other plaintiffs and seven years had passed since court ordered integration had been ruled on; their ceaseless efforts for the fair treatment of Mexican Americans were indeed worth fighting for and had a significant impact on the future course for CCISD.

When all had been said and done, Corpus Christi Independent School System would integrate their schools and abandon discriminatory and segregational practices. This is only one of many cases where Mexican Americans won civil liberties in a public school system. However, this case in particular set a precedent for Mexican Americans to be recognized as an identifiable minority group that deserved all the equal protections set forth in Brown v. Board of Education. [14]

[1] Steve H. Wilson, “Brown over ‘Other White’: Mexican Americans’ Legal Arguments and Litigation Strategy in School Desegregation Lawsuits.” Law and History Review 21, no. 1 (2003): 188, doi:10.2307/3595071.

[2] Alan Lessoff, Where Texas Meets the Sea (Texas: The University of Texas Press, 2015) 111,112.

[3] Patrick J. Carroll, Felix Longoria’s Wake (Texas: The University of Texas Press, 2003) 68.

[4] Carroll, Felix Longoria's Wake, 78.

[5] William M. Gordon, “The Implementation of Desegregation Plans Since Brown,” Journal of Negro Education 63, no. 3 (1994): 310-22, doi: 10.2307/2967183.

[6] Wilson, Law and History Review, 177.

[7] Wilson, Law and History Review, 181.

[8] Anne Dodson, “The Background of Local School Integration,” Corpus Christi Caller Times, June 6, 1971, http://docs.newsbank.com.manowar.tamucc.edu

[9] Wilson, Law and History Review, 183,184.

[10] Wilson, Law and History Review, 185.

[11] Wilson, Law and History Review, 189.

[12] Ronald Ozio, “Controversy Continues, But More Quietly,” Corpus Christi Caller Times, July 10, 1977, http://docs.newsbank.com.manowar.tamucc.edu

[13] Ronald Ozio, “Who Are the Busing Foes? It’s Hard to Determine,” Corpus Christi Caller Times, July 13, 1977, http://docs.newsbank.com.manowar.tamucc.edu

[14] Wilson, Law and History Review, 188.

Bibliography

Carroll, Patrick J. Felix Longoria’s Wake. Texas: The University of Texas Press, 2003.

Dodson, Anne. “The Background of Local School Integration.” Corpus Christi Caller Times, June 6, 1971. Accessed March 21, 2018, America’s Historical Newspapers, Archives of Americana.

Gordon, William M. “The Implementation of Desegregation Plans Since Brown.” Journal of Negro Education 63, no. 3 (1994): 310-22. Accessed March 21, 2018. doi: 10.2307/2967183.0

Lessoff, Alan, Where Texas Meets the Sea. Texas: The University of Texas Press, 2015.

Ozio, Ronald. “Controversy Continues, But More Quietly.” Corpus Christi Caller Times, July 10, 1977. Accessed March 21, 2018, America’s Historical Newspapers, Archives of Americana.

Ozio, Ronald. “Who Are the Busing Foes? It’s Hard to Determine.” Corpus Christi Caller Times, July 13, 1977. Accessed March 21, 2018, America’s Historical Newspapers, Archives of Americana.

Wilson, Steven H. “Brown over ‘Other White’: Mexican Americans’ Legal Arguments and Litigation Strategy in School Desegregation Lawsuits.” Law and History Review 21, no. 1 (2003): 145-94. Accessed March 21, 2018. doi:10.2307/3595071.